There is a lot of data out there; on the the internet, tucked away in databases, sitting patiently on the other side of a REST web service just waiting to pounce on your unsuspecting Windows Phone application that just wants to display a little slice of it all so people can read it, touch it and generally make sense of it. The problem is there is a lot of it, so what is a poor unsuspecting application to do, especially when it’s been crammed into a form factor that doesn’t allow ever expanding memory upgrades?

In this post and a few to come I’m going to explore the various ways you can work with the ListBox (the go-to control for displaying lists of data) in your application to keep it speedy and responsive. Today we’re going to start with a feature added in Silverlight for Windows Phone: Data Virtualization.

Data Virtualization

Data virtualization is the concept of only loading “just enough” data to fill out your UI and be useful to interact with. This is particularly useful if your data set is large and can’t all fit into memory at the same time. Good examples are the 3,000 images you took of various pancakes shaped like childhood cartoon characters or all 23,083 remixes of The Postal Services “The District Sleeps Alone Tonight” you have loaded up on your phone.

Data virtualization in Silverlight is accomplished when you bind a custom IList implementation to a ListBox with a data template. Let’s break that statement down by creating a very naïve virtualized list that simulates a list of 10,000 song objects.

Implement IList

This isn’t as daunting as it might seem, there are really only two methods you need to implement: Count and the indexer property. Everything else can throw NotImplemented. Count returns, well, the count of items while the indexer returns the actual item being requested by index.

Most of the magic happens in the indexer. When an item is requested you now have a chance to go off and grab your data, fabricate it (such as using a WriteableBitmap), load it from IsolatedStorage, compute it based on index or generally return whatever makes sense.

Here I’m just creating a new Song class and setting its Title to a string that matches the requested index but in reality you’d be doing some parsing/loading/fetching here.

public class Song

{

public string Title { get; set; }

public string Length { get; set; }

}

public class VirtualSongList : IList<string>, IList

{

/// <summary>

/// Return the total number of items in your list.

/// </summary>

public int Count

{

get

{

return 10000;

}

}

object IList.this[int index]

{

get

{

// here is where the magic happens, create/load your data on the fly.

Debug.WriteLine("Requsted item " + index.ToString());

return new Song() { Title = "Song " + index.ToString() };

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

}

// everything else throws NotImplemented Exception.

// .

// .

// .

}

NOTE: While the code is rather easy to implement it’s boring, mind numbingly boring so I’ve made the above implementation available for your source downloading pleasure.

Bind to ListBox

This is pretty straight-forward stuff, you’ll need to bind your new fancy list to the ListBox in question.

// Constructor

public MainPage()

{

InitializeComponent();

ItemList.ItemsSource = new VirtualSongList();

}

DataTemplate

One caveat is your ListBox needs to use a DataTemplate otherwise virtualization doesn’t kick in. The virtualization code-path needs to make a few assumptions about your data and having a DataTemplate helps it down that path. Without it all your hard work will go down the drain as the first time you bind your list every single item will be requested.

<ListBox x:Name="ItemList">

<ListBox.ItemTemplate>

<DataTemplate>

<TextBlock Text="{Binding Title}" FontSize="32" />

</DataTemplate>

</ListBox.ItemTemplate>

</ListBox>

In Action

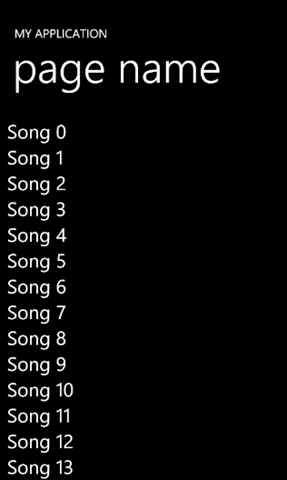

Let’s take this code for a spin. An F5 and emulator launch later and we’re looking at this pretty screen:

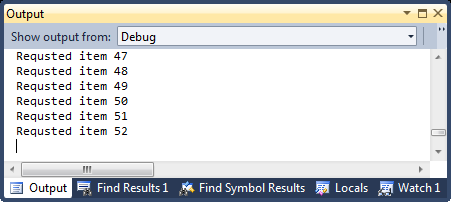

As you can see we’re using the Song created during the indexer call. To prove it’s actually virtualized I added a Debug.WriteLine to output every time an item was requested:

As you can see only 52 items were requested instead of the full 10,000. Why 52 instead of just 13? You always want a few items as buffer to give your virtualizing code a chance to actually do the work while items are being scrolled into view. For this reason we request about three page worth of data so your UI is always responsive.

Extending And Testing

A virtualized list that only returns 10,000 items is a bit limited. A better, more testable pattern would be to create a separate repository or “creator” class that actually creates, counts and manages the objects. Your list should be nothing but that, a list.

Caching

Another thing to be aware of, and this is important to pay attention to, virtualization doesn’t do any caching for you. This means if you scroll down and then back up your virtualized list will ask for index 0 again and if you have a naïve implementation you will recreate item 0 over and over again. Depending on what you’re returning you may want your repository to have some kind of object cache based on either time or current index.

When To Virtualize

If you attempt to do a lot in your indexer’s get, where you actually make the “virtual” data real, you’ll soon discover that your UI is now *worse* than it was before. That’s because as you’re scrolling it’s getting hit over and over again so if you have an expensive creation you’ll block your UI thread and everything will come to a screaming to a halt (some people say screeching halt but if I can’t interact with my UI you will hear screaming).

The general rule of thumb on when to use data virtualization is for large lists or medium lists whose items are heavy weight, such as images and expensive XAML objects. The bottom line is you just can’t have all 3,000 images loaded up at once so you need some way to give the user a feeling of a nice, continuous smooth scroll.

So how do you minimize the delay from heavy weight objects? Stay tuned for my next blog post when I talk about using proxy (some people like to say broker) objects to push as much of the real work into the background thread.